- Mammoth Grip Sprinkler Spacers. Mammoth Grip Sprinkler Spacers are used to stabilize and accurately install sprinkler heads.

- Armada Technologies Pro48 Solenoid Activator / Chatterbox and Pro210 Tone Probe. Portable, irrigation system tester. Activates valves, tests solenoids, tests wire continuity, chatters solenoids, and has a tone generator for wire identification.

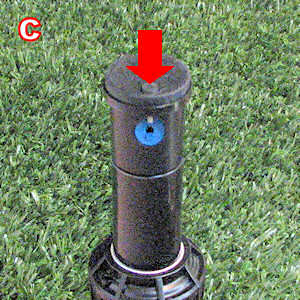

- Sprinkler Buddy Sprinkler Head Indicator. The Sprinkler Buddy keeps grass from growing next to or over the sprinkler head, thus make the sprinkler location obvious in the lawn.

All posts by Jairo Razo

Irrigation Controller or Timer Reviews

Key to common controller features in the table below:

- Stations. Maximum number of valve stations. The actual number of stations may be less depending on which model is purchased. In most cases you need one station for each automatic valve.

- Programs. Number of programs available. Each program can have different start times, operation days, and run times for the irrigation valve stations. You need to use different programs for areas with different water requirements. For example a lawn might need to be watered every other day, but drought tolerant shrubs might need watering only once a week or less. Without separate programs they would both be watered on the same days and the shrubs might drown. More programs allows more flexibility resulting in water savings and healthier plants. Most homes need at least 2 programs, one for the lawn and one for the shrubs. Few homes need more than 4 programs.

- Smart Controller. A “Smart Controller” adjusts the watering schedule by itself throughout the year. Smart controllers are quickly becoming mandatory by law in much of the Western and Southern USA. To read more on Smart Controllers see the Smart Controller FAQ. If the controller has Smart features the following key indicates what system is used:

- H Historical. Adjusts watering based on historical water use records.

- HS Historical with a sensor. Fine tunes historic data using current condition sensor.

- OS Off-site data via phone, radio, Internet, etc.

- WS Weather station. Has it’s own weather station.

- MS Uses a soil moisture sensor.

- Master Valve Has a control circuit for a master valve and/or pump start switch. An important feature if you use a pump.

- Rain Sensor Has a circuit for attaching a rain sensor. Shuts down if rain detected (typically the sensor itself is not included.)

- Non Volatile Memory is non-volatile, retains data without a battery even in a power failure.

- Delay A delay can be programmed between valve stations to allow time for slow closing valves to close fully. Another important feature if you have a pump, or if you have low water pressure.

| Manufacturer/ Product Name Click on Name to Read Review | Part No. | S t a t i o n s | P r o g r a m s | S m a r t C o n t r o l l e r | M a s t e r V a l v e | R a i n S e n s o r | N o n V o l a t i l e | S t a t i o n D e l a y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gwytech PC Timer | V 1.0 | 8 | 4 | X | X | X | X | ||

| WeatherTRAK ETplus | WTPLS-06 | 6-48 | 3 | OS | X | X | X |

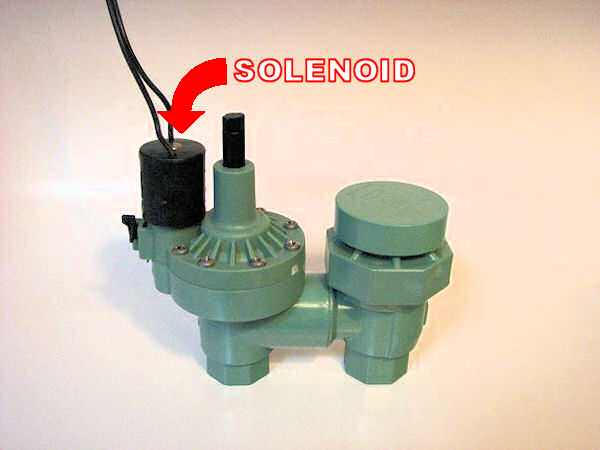

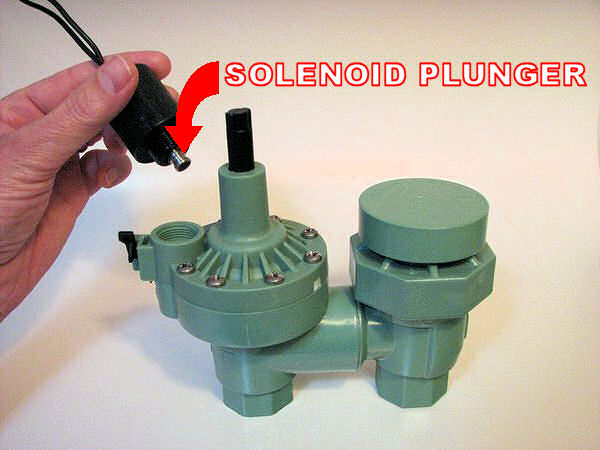

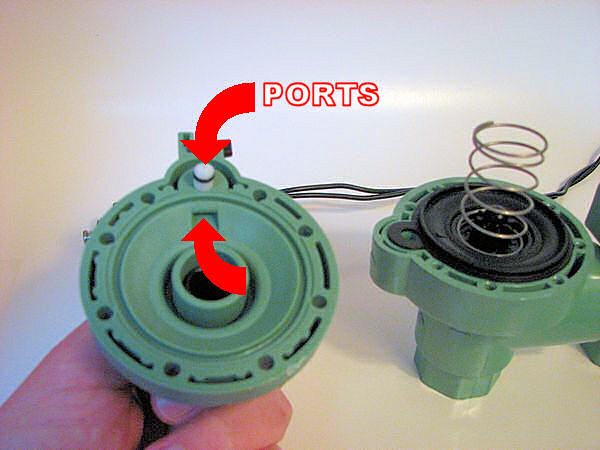

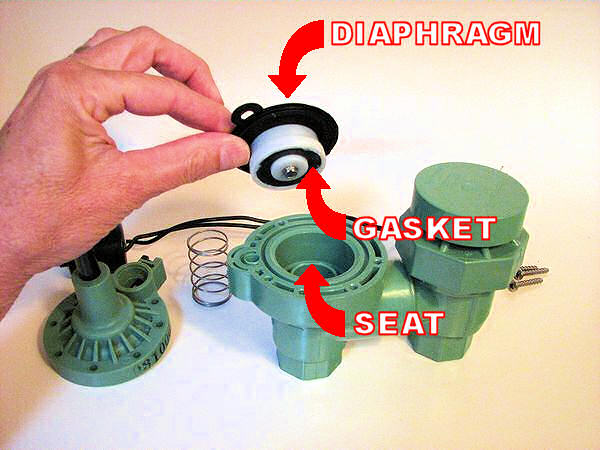

Automatic Irrigation Solenoid Valves Reviews

This page contains an index and links to reviews of automatic solenoid valves commonly used in landscape sprinkler systems and other irrigation systems.

Electric Anti-Siphon Valves

| Manufacturer | Reviews | Part No. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Champion | CL466-075, CL466P-075 CL466-100, Cl466P-100 | 3/4″ Anti-Siphon Valve 1″ Anti-Siphon Valve | |

| Hunter | Click Here for Review | ASV series | 3/4″ Anti-Siphon Valve 1″ Anti-Siphon Valve |

| Irritrol | Click Here for Review | 2711APR 2713APR 2711DPR 2713DPR | 3/4″ Anti-Siphon Valve 1″ Anti-Siphon Valve 3/4″ Anti-Siphon Valve 1″ Anti-Siphon Valve |

| Irritrol | Click Here for Review | 311A-.75 311A-1 | 3/4″ Anti-Siphon Valve 1″ Anti-Siphon Valve |

| Lawn Genie | Same as Irritrol anti-siphon valves Click Here for Review | L7034 L7010 RJ 3/4 54000 | 3/4″ Anti-Siphon Valve 1″ Anti-Siphon Valve 3/4″ Anti-Siphon Valve |

| Orbit | 57223 57224 | 3/4″ WaterMaster Anti-Siphon Valve 1″ WaterMaster Anti-Siphon Valve | |

| Rainbird | DAS-075, 075-ASVF DAS-100, 100ASVF | 3/4″ Sure Flow Anti-Siphon Valve 1″ Sure Flow Anti-Siphon Valve | |

| Rainbird | APAS-075 APAS-100 | 3/4″ Anti-Siphon Valve 1″ Anti-Siphon Valve | |

| Rain Jet Name changed to Lawn Genie | Same as Irritrol anti-siphon valves Click Here for Review | ||

| Toro Irrigation | 299-0?-03 299-0?-04 | 3/4″ Flo-Pro Anti-Siphon Valves 1″ Flo-Pro Anti-Siphon Valves | |

| WaterMaster (Orbit) | 57223 | 3/4″ Anti-Siphon Valve |

Electric Angle or Globe Valves

| Manufacturer | Reviews | Part No. | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Champion | PGA-075 PGA-100 PGA-150 PGA-200 | 3/4″ globe valve 1″ globe valve 1.5″ globe valve 2″ globe valve | |

| Hardie | Hardie is now called Irritrol | ||

| Hunter | Click Here for Review | SRV series | 1″ globe valve |

| Hunter | Click Here for Review | PGV series | 1″ globe valve 1″ angle valve 1 1/2 & 2″ combination globe/angle valves |

| Hunter | Click Here for Review | HPV-101-G HPV-101-A | 1″ globe valve 1″ angle valve |

| Hunter | Click Here for Review | ICV-101-G ICV-151G ICV-201G | 1″ globe valve 1.5″ globe valve 2″ globe valve |

| Hydro Rain (2 separate companies, different products) | (Old) Hydro Rain (of Laguna Niguel, products made pre 2000) these products are now made under the name Irritrol. —- (New) Hydro Rain (of North Salt Lake City, products made from 2005) I have not reviewed the new Hydro Rain branded products yet. | ||

| Irritrol | Click Here for Review | 2400* 2600* | 1″ globe valves 1″ angle valves |

| Irritrol | Click Here for Review | 2500T 2500TF | 1″ globe valve |

| Irritrol | Click Here for Review | 205TF | 1″ globe valve |

| Irritrol | Click Here for Review | 214B 216B 217B | 1″ combination globe/angle valve 1.5″ combination globe/angle valve 2″ combination globe/angle valve |

| Irritrol | Click Here for Review | 100-1 100-1.5 100-2 100-3 | 1″ combination globe/angle valve 1.5″ combination globe/angle valve 2″ combination globe/angle valve 3″ combination globe/angle valve |

| Irritrol | Click Here for Review | 102-1 102-1.5 102-2 102-3 | 1″ DW combination globe/angle valve 1.5″ DW combination globe/angle valve 2″ DW combination globe/angle valve 3″ DW combination globe/angle valve |

| Irritrol | Click Here for Review | 700-.75 700-1 700-1.5 700-2 | 3/4″ globe valve 1″ globe valve 1.5″ globe valve 2″ globe valve |

| Lawn Genie | Same as Irritrol 2500 series Click Here for Review | 54002 54003 54004 54005 | 1″ Globe Valve 1″ Globe Valve 1″ Globe Valve 3/4″ Globe Valve |

| Nelson (L.R. Nelson Corp.) | 7911, 7917 7931 | 1″ globe valve 1″ angle valve | |

| Nelson (L.R. Nelson Corp.) | 7951, 7971 | 1.5″ combination globe/angle valve | |

| Nelson (L.R. Nelson Corp.) | 7952, 7972 | 2″ combination globe/angle valve | |

| Nelson (L.R. Nelson Corp.) | 7953, 7973 | 3″ combination globe/angle valve | |

| Rainbird | JTV | 1″ globe valve (jar top) | |

| Rainbird | CP Series | 3/4″ & 1″ globe valves | |

| Rainbird | CPF Series | 3/4″ & 1″ globe valves | |

| Rainbird | 075-DV, 100-DV, 100-DV-SS, 100-DV-A, 100-DV-MM, 100-DV-MB, 125-DV-MB | 3/4″ & 1″ globe valves | |

| Rainbird | 100-DVF, 100-DVF-SS 100-DVF-A, 100-DVF-BSP | 1″ globe valve | |

| Rainbird | 100-PGA, 100-PGA-BSP 150-PGA, 150-PGA-BSP 200-PGA, 200-PGA-BSP | 1″ combination globe/angle valve 1.5″ combination globe/angle valve 2″ combination globe/angle valve | |

| Rainbird | 100-PEB, 100-PEB-BSP 150-PEB, 150-PEB-BSP 200-PEB, 200-PEB-BSP | 1″ globe valve 1.5″ globe valve 2″ globe valve | |

| Rainbird | 100-PESB, 100-PESB-BSP 150-PESB, 150-PESB-BSP 200-PESB, 200-PESB-BSP | 1″ DW globe valve 1.5″ DW globe valve 2″ DW globe valve | |

| Rainbird | GB Series Brass Valves | 3/4″ globe valve, 1″ globe valve, 1 1/4″ globe valve, 1 1/2″ globe valve, 2″ globe valve | |

| Rainbird | EFB-CP Series Brass Valves | 3/4″ globe valve, 1″ globe valve, 1 1/4″ globe valve, 1 1/2″ globe valve, 2″ globe valve | |

| Richdel | Richdel is now called Irritrol | ||

| Superior | Click Here for Review | 950 & 950RW Brass Valves | 3/4″ globe valve, 1″ globe valve, 1 1/4″ globe valve, 1 1/2″ globe valve, 2″ globe valve |

| Superior | Click Here for Review | 1000 series Brass Valves for Recycled Water | 3/4″ globe valve, 1″ globe valve, 1 1/4″ globe valve, 1 1/2″ globe valve, 2″ globe valve, 2 1/2″ globe valve, 3″ globe valve |

| Superior | Click Here for Review | 3000 & 3100 Brass Master Valves | 3/4″ globe valve, 1″ globe master valve, 1 1/4″ globe master valve, 1 1/2″ globe master valve, 2″ globe master valve, 2 1/2″ globe master valve, 3″ globe master valve |

| Superior | Click Here for Review | 3200 & 3300 Brass Master Valves (No Minimum Flow) | 3/4″ globe 3-way solenoid master valve, 1″ globe 3-way solenoid master valve, 1 1/2″ globe 3-way solenoid master valve, 2″ globe 3-way solenoid master valve, 2 1/2″ globe 3-way solenoid master valve, 3″ globe 3-way solenoid master valve |

| Toro Irrigation | 280-??-?4, 284-??-?4 | 1″ globe valve | |

| Toro Irrigation | 254-?6-03 254-?6-04 | 3/4″ globe valve 1″ globe valve | |

| Toro Irrigation | 53283 53381 | 3/4″ globe valve 1″ globe valve | |

| Toro Irrigation | 250-?4-03 250-0?-?4 | 3/4″ globe valve 1″ globe valve | |

| Toro Irrigation | 252-06-04 252-2?-06 252-2?-08 | 1″ combination globe/angle valve 1.5″ combination globe/angle valve 2″ combination globe/angle valve | |

| WaterMaster (Orbit) | 53285 | 3/4″ globe valve | |

| Weather-Matic | Click here for Review | N-100 series | 1″ globe valves |

| Weather-Matic | Click here for Review | 12024E-10 12024EF-10 | 1″ globe valve |

| Weather-Matic | Click here for Review | 21000CR | 1″ DW globe valve 1.5″ DW globe valve 2″ DW globe valve |

| Weather-Matic | Click here for Review | 11024E-10 11024E-15 11024E-20 | 1″ globe valve 1.5″ globe valve 2″ globe valve |

| Weather-Matic | Click here for Review | 8024BCR-07 8024BCR-10 8024BCR-12 8024BCR-15 8024BCR-20 8024BCR-25 8024BCR-30 | 3/4″ brass globe valve 1″ brass globe valve 1.25″ brass globe valve 1.5″ brass globe valve 2″ brass globe valve 2.5″ brass globe valve 3″ brass globe valve |

Notes for tables above:

- DW means the valve has special features for use with dirty water (caution–dirty is a relative term, if you can SEE the dirt you better get a good filter rather than a DW valve!!!)

- PR means pressure regulating. (Caution–the outlet pressure for the valve must be set at least 15 PSI lower than the incoming water pressure for most pressure regulating valves to work properly.)

- Valves are plastic unless noted as brass. (Do not assume brass is better, but also do not assume plastic is better!)

Common Valve Options:

Latching Solenoids

Latching solenoid option: Latching solenoids are special solenoids used most often with battery or solar operated irrigation controllers. A latching solenoid will not work with a standard irrigation controller. The latching solenoids work on a toggle principle. Each time they get an electrical pulse from the controller they either open or close. So when they get the first electric pulse they open. The next time they get a pulse they close. This saves electricity which is why battery operated controllers use them. The bad news is if they ever get “out of phase” they open when they should close and visa-versa. So the sprinklers run all day and turn off for 15 minutes each night. Opps…

3-way Solenoid

3-way solenoid option: A full explanation of what a 3-way solenoid is would require an in-depth knowledge of the hydraulic principles that make a valve work, which is a bit too much to try to explain here. So let’s just say that a 3-way solenoid is a more complex solenoid that is less sensitive to dirt or other contaminates in the water. 3-way solenoids are used on many dirty water or anti-contamination valves. Warning- most 3-way solenoids spit out a small amount of water each time the valve is opened, so be prepared for a few tablespoons up to a cup or more of water to come out. If installed indoors you’ll need a drain for the water to go into.

Dirty Water Valve

Dirty water option: An important note on “dirty water” and “anti-contamination” valves. “Dirty water” as used in the irrigation industry means water with small amounts of particulates or algae particles. As a general rule if the water looks dirty, then it is too dirty for any standard irrigation valve, including those labeled as “dirty water” or “anti-contamination” valves. You certainly don’t want to feed water into this valve, or any other manufacturer’s “dirty water” valve, that has sticks or twigs in it! Dirty water valves, such as this one, are commonly used for things like irrigation using secondary treated sewage. These valves contain internal screens to prevent debris from entering the small passages inside the valve. But remember that big stuff can still get lodged in the main passageways of the valve. Really dirty “sludge” water contains so much garbage that the screens become clogged, even if they are “self-cleaning”. The bottom line is that if you are pumping really dirty water, such as dairy sludge, you should talk to the valve manufacturer before using any valve. One more tip; when you call, talk to one of their engineering staff or a “troubleshooter”, not a salesperson! Almost every irrigation equipment manufacturer has troubleshooters that know the capabilities of their equipment better than anyone. These folks will generally give you a straight answer because they are the poor saps who have to go out and check out the problem if the valve doesn’t work!

Pressure Regulating

With this option the valve will regulate the downstream pressure to a desired maximum level. Lets say your irrigation mainline pressure is 100 PSI and you want to operate spray heads on the valve circuit controlled by this valve. At 100 PSI the spray heads would bow apart. With this option the valve can be set so that it will always keep the downstream pressure at 40 PSI or less. Like all pressure regulators the outlet pressure you set must be at least 15 PSI lower than the inlet pressure for the valve. If not, the regulator to work accurately or may not work at all. So if your mainline pressure is 45 PSI and you set the outlet for 40 PSI it won’t work very well. If the pressure at the valve inlet is 45 PSI you would ned to set the outlet pressure at 30 PSI (45-15=30). You could set the pressure lower than 30 PSI if desired, just not higher.

Rotor Type Sprinklers

How to Select the Best Rotor-type Sprinkler:

Click here for an in-depth discussion of rotor-type sprinklers and what facts you should consider when selecting one. You should read this before reading the reviews or deciding on a make or model to use.

List of Rotors & Reviews:

Click here for a list of minimum standards for a good rotor.

Click here for a description of the feature codes used in the list below.

Rotor-Type Sprinkler Heads

Features in red are optional. They cost extra and may require a special order from the factory.

| Manufacturer | Reviews | Part No. | Description | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buckner | PI11 | Pop-up Impact | WS, SR, Arc:20-340° | |

| Buckner | PI25 | Pop-up Impact | WS, SR, Arc:20-340° | |

| Buckner | Same as K-Rain K2 | G7X | 5″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, LA, CV, RC, SS, Arc:30-360° |

| Buckner | GP103 | 5″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, RC, SS, Arc:30-360° | |

| Manufacturer | Reviews | Part No. | Description | Features |

| Champion | IP-1 | Pop-up Impact | WS, SR, Arc:20-340° | |

| Champion | 6182 | Pop-up Impact | WS, SR, Arc:20-340° | |

| Champion | Same as K-Rain K2 | RO series | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, Arc:30-360° |

| Manufacturer | Reviews | Part No. | Description | Features |

| Hunter | Click here for Review | PGJ series | Small Radius Rotors w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, NP Arc:40-360° |

| Hunter | Click here for Review | PGP series | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzlePGP-ATR 2 1/4″ Pop-Up | WS, SR, FS, CC, RC, CV, NP, LA Arc:40-360° |

| Hunter | Click here for Review | PGH series | Same as PGP but 12″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, RC, CV, NP, LA Arc:40-360° |

| Hunter | Click here for Review | I-20 series | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, LA, RC, NP, SS, SO, Arc:40-360° |

| Hunter | Click here for Review | I-20-HP series | 12″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, LA, RC, NP, SS, SO, Arc:40-360° |

| Hunter | Click here for Review | MP Rotator MP?000 90-210 | Stream Rotor (Nozzle Only) | FS, CC, Arc:90-210° |

| Hunter | Click here for Review | MP Rotator MP?000 210-270 | Stream Rotor (Nozzle Only) | FS, CC, Arc:90-210° |

| Hunter | Click here for Review | MP Rotator MP?000 360 | Stream Rotor (Nozzle Only) | FS, CC, Arc:360° |

| Manufacturer | Reviews | Part No. | Description | Features |

| K-Rain | 12003 series Dial-A-Nozzle | 5″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, LA, Arc:40-360° | |

| K-Rain | 11003 series ProPlus | 5″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, LA, Arc:40-360° | |

| K-Rain | K2 9000 series | 5″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, LA, CV, RC, SS, Arc:30-360° | |

| K-Rain | K3 10000 series 15000 series | 5″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, RC, SS, Arc:30-360° | |

| Manufacturer | Reviews | Part No. | Description | Features |

| Nelson (L.R. Nelson Corp.) | Pro 5500series | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, RC, SS, Arc:40-310° | |

| Nelson (L.R. Nelson Corp.) | Pro 5512series | 12″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, RC, Arc:40-310° | |

| Nelson (L.R. Nelson Corp.) | Pro 6000 | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, NP, RC, LA, SS, Arc:40-310° | |

| Nelson (L.R. Nelson Corp.) | Pro 6012 | 12″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, NP, RC, LA, Arc:40-310° | |

| Nelson (L.R. Nelson Corp.) | Pro 6500 series | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, NP, RC, Arc:40-310° | |

| Nelson (L.R. Nelson Corp.) | Pro 7000 series | 4.5″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, RC, Arc:40-310° | |

| Nelson (L.R. Nelson Corp.) | Pro 7500 series | 4.5″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, RC, Arc:40-310° | |

| Manufacturer | Reviews | Part No. | Description | Features |

| Orbit | “Saturn III” 5300 PMR | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, Arc:40-360° | |

| Orbit | See Hunter PGP review. | “Voyager II” 5500 PR | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, RC, LA Arc:40-360° |

| Manufacturer | Reviews | Part No. | Description | Features |

| Rainbird | Click here for Review | LG-3, MG-4 Mini-Paw | Pop-up Impact | WS, SR Arc:20-340° |

| Rainbird | Click here for Review | AG-5 2045A Maxi-Paw | Pop-up Impact | WS, SR, LA,CV,NP Arc:20-340° |

| Rainbird | Click here for Review | R-50 series | 3 5/8″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, RC, LA, NP, Arc:25-350° |

| Rainbird | TDR-2 series | 3 5/8″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, Arc:25-350° | |

| Rainbird | 3500 series | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, NP, Arc:40-360° | |

| Rainbird | stripped-down version of the 3500 series | 32SA | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, Arc:40-360° |

| Rainbird | 5000 series | 4″, 6″ & 12″ Pop-Up Rotors w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, RC, LA, CV, NP, Arc:40-360° | |

| Rainbird | stripped-down version of the 5000 series | 42SA | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, RC, Arc:40-360° |

| Rainbird | Click here for Review | T-Bird series | 4 1/2″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, RC, LA, NP, Arc:30-350° |

| Manufacturer | Reviews | Part No. | Description | Features |

| Toro Irrigation | Click here for Review | 53757, 53758, 53759 | Multi-Stream Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, Arc Plates: 90-360° |

| Toro Irrigation | Click here for Review | 300 series | 300 Multi-Stream Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, NP, Arc Plates: 90-360° |

| Toro Irrigation | Click here for Review | 340 series | 340 Multi-Stream Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, NP, Arc Plates: 90-360° |

| Toro Irrigation | Click here for Review | XP300 series | XP-300 Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, NP, Arc Plates: 90-360° |

| Toro Irrigation | Same as K-Rain K2 | S800 series | 5″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, LA, CV, RC, SS, Arc:30-360° |

| Toro Irrigation | Click here for Review | S700P series | 3″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, LA, RC, NP, SS, Arc:40-330° |

| Toro Irrigation | Click here for Review | S700HP series | 10.5″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, LA, RC, NP, SS, Arc:40-330° |

| Toro Irrigation | Click here for Review | V-1550-6 series | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, LA, RC,NP, Arc:40-360° |

| Toro Irrigation | Click here for Review | V-1550-12 series | 10″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, LA, RC,NP, Arc:40-360° |

| Manufacturer | Reviews | Part No. | Description | Features |

| Manufacturer | Reviews | Part No. | Description | Features |

| Weather-Matic | Click here for Review | T3 | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, RC, NP, Arc:40-360° |

| Weather-Matic | Click here for Review | CT70 | 4″ Pop-Up Rotor w/ nozzle | WS, SR, FS, CC, CV, RC, NP, SS, Arc:40-360° |

*Caution: Part numbers for some models don’t follow in a logical order that clearly identifies the body style. Check the description to assure it is the correct sprinkler head.

Other Products related to Rotor Heads:

- Mammoth Grip Sprinkler Spacers. Mammoth Grip Sprinkler Spacers are used to stabilize and accurately install sprinkler heads.

- Sprinkler Buddy Sprinkler Head Indicator. The Sprinkler Buddy keeps grass from growing next to or over the sprinkler head, thus making the sprinkler location obvious in the lawn.

Minimum standards:

I think any that any rotor sprinkler worth spending money on should have the following features:

- Must pop-up at least 3 inches (stream height above top of case).

- Must not be a discontinued or test-run product (generally that means at least one year on the market).

- Must have positive spring retraction for the riser piston.

- Must have a wiper seal on the riser piston.

- Must have a filter screen.

- Must have a closed-case (drive unit not exposed).

- If installed in a play area it should have a rubber cover (a rubber cover is so cheap and such an obvious safety item, I can’t think of a good excuse why all rotors shouldn’t have one!)

Feature key:

The following abbreviations are used in the reference chart below for various features of the rotor models:

- WS = Wiper seal. A wiper seal around the pop-up riser keeps dirt out of the sprinkler and reduces water waste.

- SR = Spring retraction. A spring pulls the pop-up riser back into the body after irrigation.

- FS = Filter screen. A screen installed inside the sprinkler helps protect the nozzle from debris in the water which might get caught in the nozzle. This is not a substitute for cleaning out the pipe when installing! I’ve found that most of these screens are only partially effective. A lot of stuff still gets though. The junk will not clog the nozzle but on water lubricated rotor drive mechanisms it can jam in the gears.

- CV = Check valve. The check valve keeps water from draining out of the pipes through the sprinkler head when the system stops running. A “must have” feature if your irrigation is installed on a sloped area. In general, if the elevation changes more than a foot within the valve zone, I recommend you use rotors with built-in check valves. Without this feature the water in the pipes will empty out through the lowest sprinkler head every time the valve is closed. This creates puddles and mud around the lowest heads and also cause excessive air discharge the next time the sprinklers are turned on. This feature may be optional, that is, it is available but you will only get it with the sprinkler if you request it (and probably pay extra). Most check valves can be easily added as a retrofit item after the sprinkler is installed. You just unscrew the top, pull out the guts, snap in the check valve, then reassemble. No need to dig up the sprinkler. Check valve conversion kits can be difficult to obtain, and may require special ordering. If you even remotely think you may need them, it is best to just buy a model with a check valve already installed.

- NP = Non-potable water markings. Purple-colored markings are available for the sprinkler, generally with the label “Do Not Drink” on them. In most cases this is a replacement cap for the sprinkler, some are snap on covers that snap over the standard cap. Purple is the universal color for identifying a water source that is unsafe for human contact. In many places treated sewage and “gray water” (water from canals or untreated waste water from sinks or showers) are used for irrigation water, thus these warning labels are needed. This item may be optional, that is, you will only get it with the sprinkler if you request it (and probably pay extra).

- VR = Vandal Resistant. Has a feature that makes the sprinkler more vandal resistant. In most cases this is a lock screw that prevents easy disassembly or removal of the sprinkler without a special tool, probably an Allen wrench. Sometimes a metal cap is also part of the package. This feature may be optional, that is, it is available but you will only get it with the sprinkler if you request it (and probably pay extra).

- CC = Closed-Case. This means the drive mechanism that operates the sprinkler is not exposed at any time. An exposed drive unit can get stuff caught in it and jam. Bermuda and St. Augustine grass are particularly tough on open-case rotors as the grass grows into the drive mechanism. An example of an open-case rotor is a impact sprinkler head (the type with the arm that splashes into the water stream to move the stream back and forth.) A pop-up impact head is considered open-case because the mechanism is exposed while it is operating and grass easily gets into the cases. (Professional landscape maintenance people often refer to them as “rat traps”.)

- Arc:40-360° = Adjustable Arc. The first number is the minimum arc, the second is the maximum. If the maximum is not 360°, there is a separate non-adjustable full-circle model you must use for full circles.

- Arcs plates: Means that multiple arcs are available, but only at fixed intervals (not adjustable). A set of plates comes with the head, or is purchased separately, and you install the plate for the arc that best fits the shape of the area watered.

- LA = Low Angle Nozzles. Low angle nozzles are available. These are useful in windy areas. The lower angle means a shorter radius, so the heads will need to be installed closer together. This feature may be optional, that is, it is available but you will only get it with the sprinkler if you request it (and probably pay extra).

- SS = Stainless Steel Riser. The riser (the part that pops up) has a stainless steel sleeve around it. The stainless steel wears better in sandy soils where the sand can scratch the plastic riser and cause the wiper seal to leak. The stainless steel sleeve may also reduce damage from other sources (like mowers), although I have not found that it really helps that much. Typically the stainless steel sleeve is made from very thin metal. This feature may be optional, that is, it is available but you will only get it with the sprinkler if you request it (and probably pay extra).

- SO = Shut Off Valve. A small valve inside the sprinkler allows you to shut off the water to the nozzle in order to change nozzles. This is a big convenience on large sprinkler systems where it would be a pain to go shut off the valve so you can replace a nozzle in a sprinkler head. This feature may be optional, that is, it is available but you will only get it with the sprinkler if you request it (and probably pay extra).

- RC = Rubber Cover. The top of the sprinkler has a rubber cover over it to lessen the chance of injuries should someone fall on it. Highly recommended if you have kids. This feature may be optional, that is, it is available but you will only get it with the sprinkler if you request it (and probably pay extra).

- Robot. Sometimes called robot sprinklers, these sprinklers direct a stream of water to fall on specific spots. This works something like when you use a hose to water the yard, and you move the no

Spray-Type Sprinkler Reviews

How to Select the Best Spray-Type Sprinkler:

Click here for an in-depth discussion of spray-type sprinklers and what facts you should consider when selecting one. You should read this before reading the reviews or deciding on a make or model to use.

List of Fixed Spray Type Sprinklers & Reviews:

Click here for a list of minimum standards for a good spray sprinkler.

Click here for a description of the feature codes used in the list below.

Note that many of the sprinkler model series listed include shrub and 2″ pop-up bodies, which do NOT meet my minimum standards.

| Manufacturer | Review | Part No. | Description | Features (optional if red) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buckner by Storm | Does not meet my minimum standards | 18 | 1″ Pop-up body (NS) | Brass, gravity retraction |

| Buckner by Storm | Does not meet my minimum standards | BPHM | 2″ Pop-up body (NS) | Brass, gravity retraction,FS,UF |

| Buckner by Storm | SP3A | 3″ Pop-up body (NS) | FS,UF | |

| Manufacturer | Review | Part No. | Description | Features (optional if red) |

| Champion | Does not meet my minimum standards | 18 | 1″ Pop-up body | Brass, gravity retraction |

| Champion | Does not meet my minimum standards | 2102 | 2″ Pop-up body | WS,SR,FS, |

| Champion | Click for Review | FP Series | 2″,4″ Pop-up body w/ nozzle | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF |

| Manufacturer | Review | Part No. | Description | Features (optional if red) |

| Hit Products/RainPro | 700 series | 2″,3″,4″,6″,12″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF or UM,SI(12″)CV,,NP | |

| Hit Products/RainPro | 900 series | 2″,3″,4″,5″,6″,12″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF or UM,CV,PR,SI(6″ & 12″),NP | |

| Hit Products/RainPro | 900T series | 7″,13″ Telescoping Pop-up body (NS) (body is shorter) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF or UM,CV,PR,SI(6″ & 12″),NP | |

| Hit Products/RainPro | HP series | 2″,4″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,CV | |

| Manufacturer | Review | Part No. | Description | Features (optional if red) |

| Hunter | Click for Review | PS Ultra series | 2″, 4″, 6″, Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,MP,UF, CV |

| Hunter | Click for Review | SRS-xx (discontinued) | 2″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, CV,NP |

| Hunter | Click for Review | PRO Spray series; | 2″,3″,4″,6″,12″, Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, CV,NP |

| Hunter | Click for Review | PRS series; | 4″,6″,12″, Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM,PR MP,UF, CV,NP |

| Hunter | Click for Review | INST-xx (discontinued) | Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,PR, CV,NP |

| Hunter | Click here for Review | MP Rotator MPxxxx | Stream Rotor (Nozzle Only) | FS, CC, Arc:90-210° |

| Manufacturer | Review | Part No. | Description | Features (optional if red) |

| Irritrol | Click for Review | SL Series | 2″,4″,6″ Pop-up body | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, CV |

| Irritrol | Click for Review | HS3 | 3″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, CV,NP |

| Irritrol | — | I-PRO Series | 3″,4″,6″,12″, Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, SI,CV,NP,PR |

| Manufacturer | Review | Part No. | Description | Features (optional if red) |

| Orbit note –> | Orbit’s inconsistent product names and part numbers make them near impossible to list or review. There are many products on the store shelves that do not appear on their website. It is possible they assign custom and exclusive names & part numbers for large store chains. | |||

| Orbit (Watermaster) | Click for Review | 54115 54118N 94230 | 2″,4″ Pop-Up w/ nozzle “Hard Top” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,VR |

| Orbit (Watermaster) | Click for Review | 54113, 54114N | 2″, 4″ Soft Top Pop-Up w/ nozzle | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF |

| Orbit (Watermaster) | Click for Review | 54100-54117N, 54459, 94101, 94231-94232 | Orbit Pro 5400 series 2″,4″,6″,12″ Pop-Up w/ nozzle | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF |

| Orbit (Watermaster) | — | 91037,91038 | Orbit Eco-Stream Rotator series 4″ Pop-Up w/ nozzle | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF |

| Orbit (Watermaster) | — | 55137,55138 | Orbit Pressure Regulating Eco-Stream Rotator series 4″ Pop-Up w/ nozzle | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,PR |

| Orbit (Watermaster) | — | 54221 through 54245 | 400 Series SLPU 2″,4″ Pop-Up w/ brass nozzle | WS,SR,FS |

| Orbit (Watermaster) | — | 54181 through 54196, 54280 – 54283 54580 – 54583 94152 through 94178 | 400 Series SLPU 2″,4″ Pop-Up w/ nozzle | WS,SR,FS |

| Orbit (Watermaster) | — | 94097 through 94513 | Orbit Slim Springloaded Series 2″,4″ Pop-Up w/ nozzle | WS,SR,FS |

| Orbit (Watermaster) | Click for Review | 54228 through 54266 | Orbit Economy Series 2″,4″ Pop-Up w/ nozzle | WS,SR,FS |

| Orbit (Watermaster) | Does not meet my minimum standards | Brass Pop-up 54072,54071,54070 | 1″ Pop-Up w/ nozzle | Brass, gravity retraction |

| Orbit (Watermaster) | Does not meet my minimum standards | Plastic Pop-up with Brass Nozzle 54029,54028,54027 | 1 3/4″ Pop-Up w/ nozzle | Gravity retraction |

| Manufacturer | Review | Part No. | Description | Features (optional if red) |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | SP-25 series SP-25-AP | 2 1/2″ Pop-up body w/ nozzle | WS,SR,FS,MP,UF |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | SP-40 series SP-40-AP | 4″ Pop-up body w/ nozzle | WS,SR,FS,MP,UF |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1802 series | 2″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, PR,PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1803 series | 3″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, PR,PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1804 series | 4″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, PR,PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1806 series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,SI, PR,PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1812 series | 12″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,SI, PR,PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1804-SAM series | 4″ Pop-up body (NS) “Seal-A-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,CV, PR,PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1806-SAM series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) “Seal-A-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,SI,CV, PR,PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1812-SAM series | 12″ Pop-up body (NS) “Seal-A-Matic” | WS,SR,F,RM, MP,UF,SI,CV, PR,PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1804-PRS series | 4″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,PR, PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1806-PRS series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,SI,PR, PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1812-PRS series | 12″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,SI,PR, PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1804-SAM-PRS series | 4″ Pop-up body (NS) “Seal-A-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,CV,PR, PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1806-SAM-PRS series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) “Seal-A-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,SI,CV,PR, PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | 1812-SAM-PRS series | 12″ Pop-up body (NS) “Seal-A-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,SI,CV,PR, PCD,NP,VR |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | US-2 series | 2″ Pop-up body (NS) “UNI-Spray” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, CV |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | US-4 series | 4″ Pop-up body (NS) “UNI-Spray” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, CV |

| Rainbird | Click for Review | US-6 series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) “UNI-Spray” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, CV |

| Rain Pro | For RainPro sprinklers see “Hit Products” above. | |||

| Richdel | Richdel products are now made under the “Irritrol – Lawn Genie” name. | |||

| Sprinklites | Click for Review | Micro-Sprinklers & Lights | ||

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 53100 53101 53102 53104 53105 53106 53732 | 3″ Pop-up body w/ nozzle “570 Series” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 53700 53309 53699 53733 | 4″ Pop-up body w/ nozzle “570 Series” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 53395 body | 2″ Pop-up body (NS) “570 Series” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 53396 body | 3″ Pop-up body (NS) “570 Series” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 53397 body | 4″ Pop-up body (NS) “570 Series” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 53398 body | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) “570 Series” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,SI |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 53710 body | 12″ Pop-up body (NS) “570 Series” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,SI |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-2P series | 2″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM, PR,PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-3P series | 3″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM, PR,PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-4P series | 4″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM, PR,PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-6P series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,SI, PR,PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-12P series | 12″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,SI, PR,PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-2P-COM series | 2″ Pop-up body (NS) “Check-O-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,CV, PR,PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-3P-COM series | 3″ Pop-up body (NS) “Check-O-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,CV, PR,PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-4P-COM series | 4″ Pop-up body (NS) “Check-O-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,CV, PR,PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-6P-COM series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) “Check-O-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,CV,SI, PR,PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-12P-COM series | 12″ Pop-up body (NS) “Check-O-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,CV,SI, PR,PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-PRX-4P series | 4″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,PR, PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-PRX-6P series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,PR, PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-PRX-64P-SI series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,PR,SI, PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-PRX-4P-COM series | 4″ Pop-up body (NS) “Check-O-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,PR,CV,PR, PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-PRX-6P-COM series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) “Check-O-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,PR,CV,PR, PCD,NP |

| Toro Irrigation | Click for Review | 570Z-PRX-6P-SI-COM series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) “Check-O-Matic” | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UM,PR,CV,PR,SI, PCD,NP |

| WaterMaster | For WaterMaster products see “Orbit” above. | |||

| Weather-Matic | Click for Review | LX3 series | 3″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, NP |

| Weather-Matic | Click for Review | LX4 series | 4″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, NP |

| Weather-Matic | Click for Review | LX6 series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, NP |

| Weather-Matic | Click for Review | LX12 series | 12″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF, NP |

| Weather-Matic | Click for Review | LX4-CV series | 4″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,CV, NP |

| Weather-Matic | Click for Review | LX6-CV series | 6″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,CV, NP |

| Weather-Matic | Click for Review | LX12-CV series | 12″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM, MP,UF,CV, NP |

| West Ag | 47602 | 2″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM | |

| West Ag | 47603 | 3″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM | |

| West Ag | 47612 | 12″ Pop-up body (NS) | WS,SR,FS,RM | |

*Caution: Part numbers for these products don’t appear to follow in a logical pattern that clearly identifies related products. Don’t rely on the part numbers alone!!! Carefully check the descriptions, product labels, and look over the product itself to assure you are getting the correct item.

(NS) means nozzle sold separately.

Other Products related to Spray Heads:

- Mammoth Grip Sprinkler Spacers. Mammoth Grip Sprinkler Spacers are used to stabilize and accurately install sprinkler heads.

- Sprinkler Buddy Sprinkler Head Indicator. The Sprinkler Buddy keeps grass from growing next to or over the sprinkler head, thus it makes the sprinkler location obvious in the lawn.

Minimum standards:

It is my opinion that any spray sprinkler worth spending money on should have the following features:

- Pop-up at least 3 inches (stream height above top of the case).

- Not be a discontinued or test-run product (generally that means at least one year on the market).

- Positive spring retraction for the riser piston. Gravity retraction results in mowed-off nozzles.

- A wiper seal on the riser piston.

- A filter screen.

- Matched precipitation rate nozzles.

Without the above features a sprinkler is not a bargain at any price, maintenance and repairs will cost you more than it would have to just buy a good-quality sprinkler.

Note:

I have not reviewed sprinklers and nozzles separately. It is assumed the sprinkler body will be used with the standard nozzle recommended by the manufacturer. In other words, if you use an ABC brand model ZZZ series body, I assume you will use it with a nozzle supplied by ABC brand for use with their ZZZ series body. The reason I point this out is that the nozzles for many spray-type sprinklers are interchangeable with those made by other manufacturers. They tend to have either “Toro style” nozzles with male threads on the nozzle, or “Rainbird style” nozzles with female threads on the nozzle. In general, I don’t recommend mixing different brands of nozzles and bodies.

Feature key:

The following abbreviations are used in the reference chart below for various features of the spray sprinkler models:

- WS = Wiper seal. A wiper seal around the pop-up riser keeps dirt out of the sprinkler and reduces water waste.

- SR = Spring retraction. A spring pulls the pop-up riser back into the body after irrigation.

- FS = Filter screen. A screen installed inside the sprinkler helps protect the nozzle from debris in the water which might get caught in the nozzle. This is not a substitute for cleaning out the pipe when installing! Most screens are only partially effective.

- RM = Ratchet mechanism. Ratcheting allows the riser to be turned independent of the body. To realign the spray direction you don’t need to turn the entire sprinkler, just the riser. The ratcheting mechanism holds it in the new position. Sometimes called a “friction collar” or “adjustable stem position”.

- MP = Matched precipitation rate nozzles. You can mix various nozzles made by the manufacturer on the same valve zone. For example you could use a 10′ radius quarter circle, 15′ radius full circle, and a 4’x15′ strip spray nozzle all on the same valve zone and the water application uniformity remains constant. Without this feature you get wet and dry areas and lots of wasted water.

- UM = Universal male thread nozzle. This sprinkler uses universal male thread pattern nozzles. That means the nozzle will fit on any brand or model spray sprinkler that also uses universal male nozzles. I strongly recommend that all the spray-type nozzles on a valve zone be made by the same manufacturer. The matched precipitation rates of Brand A nozzles will probably not match those of Brand B.

- UF = Universal female thread nozzle. This sprinkler uses universal female thread pattern nozzles. That means the nozzle will fit on any brand or model spray sprinkler that also uses universal female nozzles. I strongly recommend that all the nozzles on a valve zone be made by the same manufacturer. The matched precipitation rates of Brand A nozzles will probably not match those of Brand B.

- Sediment basin or trap. A sediment basin is a recessed area at the bottom of the sprinkler body where sediment can settle and become trapped. When the sprinkler is turned off, small grains of sand and other particles (sediment) that were caught on the nozzle screen often drop off the screen and settle down to the bottom of the sprinkler. Then the next time the sprinkler is turned on the swirling water rushing through the sprinkler body and riser pushes this sediment back up and eventually it again gets stopped by the nozzle screen. This process repeats each time the sprinkler is run. A settlement basin or trap is a deep recessed area in the bottom of the sprinkler body where this sediment can settle out away from the turbulent flow and it will not be repeatedly blown up into the nozzle screen. This helps the screen stay cleaner and also reduces abrasive wear on the internal parts of the sprinkler that result from sediment repeatedly being swirled up against them.

- CV = Check valve. The check valve keeps water from draining out of the pipes through the sprinkler head when the system stops running. A “must have” feature if your irrigation is installed on a slope or hillside. Without this feature the water in the pipes will drain out every time the valve is closed. This creates puddles or mud pits around the lowest heads where the water drains out. It also causes excessive air discharge the next time the sprinklers are turned on (the sprinklers spit, burp, and cough, which is not good for them or the pipes.) This feature may be optional, that is, it is available but you will only get it with the sprinkler if you request it (and probably pay extra). Most check valves can be easily added as a retrofit item after the sprinkler is installed. You just unscrew the top, pull out the guts, snap in the check valve, then reassemble. No need to dig up the sprinkler. Retrofit check valves can be difficult to find, you may need to special order them from the factory.

- PCD = Pressure Control Discs. These small disks fit into the bottom of the nozzle or are built into the screen. They are essentially a rubber disk with a small hole in it that restricts the water flow. They control the water pressure and flow into the nozzle. They are very handy for reducing the radius of a spray-type sprinkler and they work much, much better than the radius reduction screws on the nozzles. The sprinkler manufacturer will have a chart showing which disc to use with each nozzle to give the exact radius you need. I use PCDs to adjust the radius on all my spray sprinkler systems. If you adjust the radius of a sprinkler using the screw on top of the nozzle, and then the next time you turn it on the sprinkler no longer sprays water, installing a PCD will cure the problem. PCDs are not generic, you must get the specific one made for your brand and model of spray head.

- PR = Pressure regulation. An built-in pressure regulator maintains uniform pattern under varying pressures. These are basically for correcting problems with existing sprinkler systems. Unless installed on a hillside, a well-designed system shouldn’t have pressure variations in it that would require a regulator at the sprinkler. It is generally less expensive to utilize a single pressure regulator at the valve or at the water source. Exception: this pressure regulation feature is helpful when you have sprinklers installed on a steep hillside where the sprinklers at the bottom of the hill will have much more pressure than those at the top. This feature may be optional, that is, it is available but you will only get it with the sprinkler if you request it (and probably pay extra).

- SI = Side inlet. An optional side inlet allows the pipe to be installed into either the side or bottom of the sprinkler. This allows the use of a shallower trench. Warning: If you use the side inlet it is very difficult to replace the sprinkler if it breaks! On many brands the pressure regulation and check valve features will not work if you use the side inlet. In general I do not advise using the side inlets. All sprinklers that have a side inlet also have a bottom inlet, so having a side inlet isn’t something to avoid when selecting a sprinkler. It is something to avoid using when you install them! Many 6″ pop-ups and most 12″ pop-ups come with a side inlet whether you want it or not.

- NP = Non-potable water markings. Purple-colored markings are available for the sprinkler, generally with the label “Do Not Drink” on them. In most cases this is a replacement cap for the sprinkler, some are snap on covers that go over the standard cap. Purple is the universal color for identifying a water source that is unsafe for human contact. In many places treated sewage and “gray water” (untreated waste water from sinks or showers) are used for irrigation water, thus these warning labels are needed. This item may be optional, that is, you will only get it with the sprinkler if you request it (and probably pay extra).

- VR = Vandal Resistant. Has a feature that makes the sprinkler more vandal resistant. In most cases this is a lock screw that prevents easy removal of the sprinkler without a special tool, probably an Allen wrench. Sometimes a metal cap is also part of the package. This feature may be optional, that is, it is available but you will only get it with the sprinkler if you request it (and probably pay extra).

Irrigation Product Listings & Reviews

Select a Product Review Category:

Product reviews are separated into categories based on the type of product. Click on the type of product you want to research below:

Fixed Spray-Type Sprinklers

Spray-type sprinklers spray a fan of water out of the nozzle, similar to a shower head. They are typically spaced up to 18 feet apart in the sprinkler system.

Rotor-Type Sprinklers

Rotor-type sprinklers have one or more moving streams of water that rotate around the sprinkler head. They are typically spaced from 18 to 45 feet apart. Even larger rotors designed for parks and golf courses are spaced up to 90 feet apart. You need a professional designer for these, even a minor design error will result in huge dry spots!

Valves

Electric solenoid valves used for turning on irrigation circuits (sprinklers or drip emitters.) Includes anti-siphon, angle, and globe type valves.

Controllers

Controllers are fancy timers used to turn on and off automatic valves.

Tools, Accessories, Etc.

Accessories, tools, and other products that don’t fit into one of the above categories.

Common Questions about the Listings & Reviews

Are these reviews biased?

Of course! Expect that any evaluation of any product will be biased by the reviewer’s own personal experiences with the product, observation of installations where the product is used, and/or the experiences related to by others.

Why are there question marks in some of the part numbers?

A question mark character (?) in a part number represents a place holder for ANY letter or number. For example, a product for which I list a part number of 531?? could represent any of the following: 53100, 53190, 531AZ, 531ZA, 531A1, 5319A, etc. Using a variable is simpler than showing many different part numbers that are all essentially the same product with only a minor variation, such as different sizes.

Even more confusion: Sometimes manufacturers repackage their products for specific stores using custom part numbers. Some manufacturer’s use part numbers that make little sense at all (at least no logic that I can figure out!) A number of products are re-branded to carry the name of a different manufacturer, so you will find the exact same product with different brand names on it. All of these practices tend to confuse things. I have tried to include each such item under all the names and part numbers used, however it is just not possible for me to know all of them.

How to Replace Your House Water Supply Pipe

Often a small water supply pipe size between the water company’s big water main in the street and your house results in a low flow to the house. This can add a lot of cost to your new sprinkler system, as a lower flow means you will need more valve circuits. This FAQ explains how much benefit to expect from changing to a larger size house water supply pipe, and how to install the new pipe if you decide it would be beneficial. This FAQ is a sub-page to the City Slicker Water webpage, which is part of the tutorial on how to design a sprinkler system. While written in relationship to irrigation systems, the information here applies to any situation where you want to achieve a greater water flow to the house. It also should be helpful if you just need or want to replace the water supply pipe for the house.

Before you begin any digging call 811. This is a FREE service available everywhere in the USA. “Every digging job requires a call – even small projects like planting trees or shrubs. If you hit an underground utility line while digging, you can harm yourself or those around you, disrupt service to an entire neighborhood and potentially be responsible for fines and repair costs.” See the 811 website for more details. They will come out and mark the locations of all the underground utilities for you. In addition to helping you avoid accidentally digging up a utility pipe or wire, this will also help you locate exactly where your existing water supply pipe is located! Again, both the phone call and the service are free.

Before rushing out to replace the existing water supply pipe with a larger pipe, I suggest that you dig up some of the existing supply pipe and see what size it actually is underground. Often a larger pipe size (probably plastic) is used for the underground portion of the pipe, with a smaller size metal pipe at the end where the pipe comes out of the ground or extends into the basement. If all but 5 feet or so of the supply pipe is a larger pipe size, you probably don’t need to replace it. In this case the larger pipe size you found underground can be used for the “New Replacement Pipe Size” when calculating a new Maximum Available GPM using the table below.

Potential New Maximum Available GPM Values

If you don’t have a water meter, use the shut-off valve size

or smallest existing supply pipe size (whichever is smaller) in place

of the water meter size.

| Water Meter Size | New Replacement Pipe Size | Maximum Available GPM when a new supply pipe is installed | |||

| Using new SCH 40 PVC supply pipe | Using new PE (SDR-7) supply pipe* | Using new Type L copper supply pipe | Using new PEX supply pipe | ||

| 5/8″ | 1″ | 15 GPM | 15 GPM | 15 GPM | 15 GPM |

| 3/4″ | 1″ | 17 GPM | 17 GPM | 17 GPM | 17 GPM |

| 3/4″ | 1 1/4″ | 20 GPM | 20 GPM | 20 GPM | – |

| 1″ | 1 1/4″ | 33 GPM | 32 GPM | 27 GPM | – |

New pipe sizes larger than those shown in the table above do not result in a higher Maximum Available GPM value. However, they may help you by reducing the pressure loss, which can also be beneficial. The Sprinkler Design Tutorial will explain this.

* PE pipe is not recommended. PE has a low burst pressure, and generally PEX pipe is now used in situations where PE was formerly used.

“Maximum Available GPM” is a value used in the Sprinkler System Design Tutorial at IrrigationTutorials.com. It is a measure of the maximum SAFE flow that the house water supply pipe can accommodate. It is possible to force more water through the pipe, however doing so may cause major damage to both the pipe and house’s plumbing system over time. See the tutorial on Water Hammer and Air in Pipes for more information on pipe damage.

The table above is only for use in situations where the water is supplied to multiple households by a water supplier, such as a municipal water system. It is not suitable for use when water is supplied from on-site wells, streams, ponds, etc. For calculating how much water is available using an on-site pump (like with a well) see the Country Bumpkin webpage, for gravity flow sources see the Backwoods Water webpage.

Not all types of pipe listed are legal to use in all locations. Local building authorities regulate through building codes what type of pipe may be used. Codes change and it may no longer be legal to replace the pipe with the same type that was previously used. Local specialized plumbing stores may be able to help you with code compliance, however it has been my experience that advice on codes from larger regional and national outlets is often not correct. I recommend that you contact your local building authorities for advice on what type of pipe to use, often this requires just a simple phone call to them. Many will also offer very valuable tips and suggestions, be sure to also ask how deep the pipe must be buried.

How to replace your water supply line:

In most places a plumbing permit is required to replace the water supply pipe or even to simply cut into it. Contact your local building authorities for details.

Remember that the water supply pipe carries the water you and your family drink! It is important to be careful not to get dirt into it when working. After completion of your work be sure to turn on all your water faucets for several minutes to flush out any dirt or other contaminates. You should sterilize the pipes before using the water from them for drinking. There are products available at plumbing stores for this. Be sure to buy the pipe sterilizer and read the instructions before you start work as you may need to put the sterilizer into the pipes before you reconnect them!

Water mains, Goosenecks, and Corporations Stops

The water company has a large pipe someplace out there that is called the “water main”. It is probably 6 inches or larger in diameter and located in the street or alley. From the water main a smaller pipe goes to your property. This smaller pipe is referred to as a “gooseneck”. At the end of the gooseneck is a shutoff valve called a “corporation stop”. The corporation stop is typically installed near your property line. The idea is that the corporation stop marks the dividing point between you and the water supplier. The pipe coming into the corporation stop belongs to the water supplier. The pipe going out of it typically belongs to the property owner. The corporation stop is usually located in a box or at the bottom of a sleeve with a round plastic or metal cap on it. The cap may only be 4″ in diameter and hard to find. Often it will be covered with dirt or grass, so you will need to poke around to find it, try probing the ground with a pitchfork, metal rake, or screwdriver. Look for a mark engraved into the curb or street pavement indicating the location. The corporation stop will probably be buried below the frost line, so it may be several feet deep in colder areas.

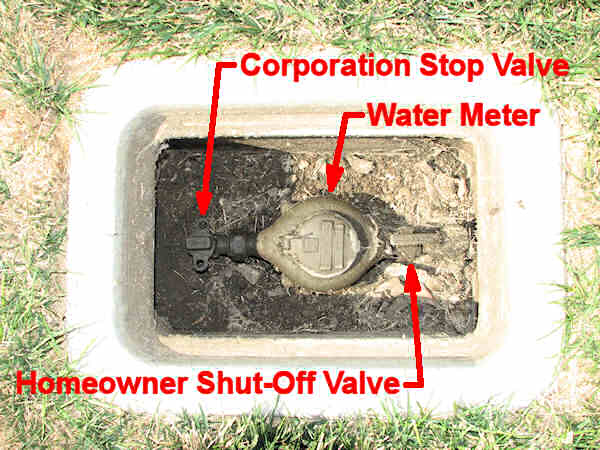

![]()

The corporation stop (often abbreviated as “corp stop”) serves as the water company shut-off valve for your house. It is usually operated using a special key or wrench in order to prevent unauthorized use. Fortunately, you can buy a wrench for it at most hardware stores. Get out a flashlight and look at top of the corporation stop first to see what shape the operating nut is, as there are several styles. Also note how deep it is so you can get a wrench with a long enough handle to reach it. Most use a slotted wrench that fits over a raised rectangular shaped bar, like the one in the photo below. If you’re really lucky, it will have a normal handle on it, but don’t bet on it! In some cases you have enough room to operate the corporation stop using a standard pipe wrench. Another trick is to use a basin wrench (a special wrench used to install faucets on sinks) to operate it. You will probably also notice a couple of holes on the corporation stop that align with each other when the valve is in the closed position. These allow the water company to padlock it closed if you don’t pay your water bill! Most corporation stops are hard to turn, so you may need to put some muscle into it. You may be able to get the water company to send someone out to close and open it for you. Often they will do this for free (especially if you ask nice, and you have a good record of paying your water bill on time!)

Photo of an underground water service utility box

containing a corporation stop, water meter, & homeowner shut-off valve.

The photo above is of a particularly nice set-up. Not only is there a corporation stop but there is also a homeowner shut-off valve with an easy to use handle. No need to use a special key, the homeowner can turn off the water themselves without tools in an emergency. I cleaned up the inside of this box before taking the photo. A valve box like this will often have ants, spiders and other disgusting stuff in it so be careful when opening them up. I even found a dead turtle in one once!

Sometimes in cold weather areas there is not a corporation stop located outside. The corporation stop is in your house, usually in the basement, crawl space, or a utility room. In this case you’re pretty much screwed, because the water service pipe is likely owned by the water company and even if it isn’t you can’t easily shut off the water to replace it. Before giving up, call your water company directly (use their local customer service number, not 811) and ask if they have a shut-off someplace between their mainline and your house. Maybe you just couldn’t find it. As a last resort, ask them if they will install a new, larger supply pipe for you. Most of the time they will, but they probably will charge you for doing it. Don’t be surprised if they refer you to a plumbing company to actually do the work.

Add a Second Pipe or Replace the Original Pipe?

How you proceed from here depends on the current layout of your water supply, your budget, and future maintenance concerns. Select the method below that best applies to your needs.

The water meter is installed right next to the corporation stop, or you don’t have a water meter.

- You can simply tap into the existing water supply pipe right after the water meter. Then install a brand new larger size pipe to the sprinkler system. The pipe leading to the irrigation system would be the “new” supply line, using the revised GPM from the table above. The existing supply line to the house would remain unchanged, and the existing flow to the house would remain unchanged. Only the sprinkler system would get the increased flow.

- Tap into the existing supply pipe right after the corporation stop/water meter and install a new second pipe to the house parallel to it. About a foot out from the house connect the new pipe back into the old, smaller pipe leading into the house. That way you don’t need to change any of the pipe in the house walls. This creates two supply pipes side-by-side to the house, with the water going through both of them. The advantage is that this saves some money, as the new pipe can be the same size as the old pipe. The water will go through both of the pipes, so the flow will be much greater than previously (but not doubled, other restrictions still exist, such as the gooseneck and corporation stop.) The downside is that you will now have two separate pipes going to the house. That means twice as much pipe that can break or leak someday. Plus the old pipe will still be there and because it is old, it is more likely to leak or break. Because this method creates future problems, it is not recommended by most professionals.

- Remove the existing water supply pipe between the corporation stop/water meter and the house and replace it completely with a new, larger pipe. About a foot out from the house connect the new pipe to the old, smaller pipe leading into the house. That way you don’t need to change any of the pipe in the house walls. This is the most common method used and is generally the best option.

The water meter is installed more than five feet away from the corporation stop (typically inside the house.)

The options for pipe replacement are essentially the same as those above, however in this case you need to replace the pipe between the corporation stop and the meter. Typically in this situation the meter is inside the house. However, if the meter is someplace out in the yard you will also need to replace the pipe between the meter and the house.

It is much easier if you don’t actually replace the short section of pipe that goes into the house through the wall or floor. Reconnect the new pipe to the old, smaller pipe about a foot outside of the house wall. That leaves a short section of the old pipe going into the house, but is a lot easier than replacing the pipe through the wall or floor. The water will squeeze through the short section and it will work fine as long as there isn’t more than 5 feet of old pipe left between the point you connected the new pipe and the water meter. If there is more than 5′ left, you will need to install new pipe through the wall, or replace the old pipe inside the house once it is through the wall. In other words you leave a short section of the old pipe going into the house through the wall. Once inside it is easier to install a new, larger pipe. You will tap in your new sprinkler system as close as possible after the water meter. Unfortunately, you will have to route the new sprinkler supply pipe out through the wall, which means you will have to drill a hole in the wall. Be sure to seal the hole around the pipe with a good quality flexible water-proof caulking compound! The pipe will move as it expands and contracts, so the caulk needs to remain flexible after it has cured. (Do not use cement for sealing the hole! Standard cement, plaster, and concrete mixes are NOT waterproof!)

Other Items to Consider

Plastic pipe must generally be installed at least 18 inches deep, measured from the top of the pipe to the soil level. All pipe should be installed below the frost line. In some areas that might be 4 feet or more deep. Your local building authorities will have specific requirements on how deep the pipe must be.

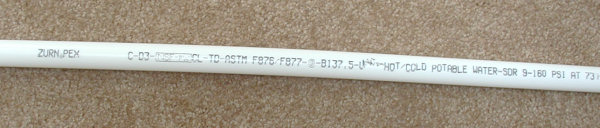

![]()

Well, that’s it for this FAQ. Have fun, and remember, safety first when digging and working with trenches. Follow all OSHA requirements. See OSHA’s guide to working around trenches.

Stopping Low Head Drainage Sprinklers that Spit Air

What Is Low Head Drainage?

Water that flows onto the sidewalk or curb after the sprinklers turn off, but then stops after a few minutes, is due to a phenomena called “low head drainage”. This occurs when the sprinkler system is installed on a sloped area. The slope does not need to be very high, a change of elevation of less than a foot will often create low head drainage. After the sprinklers are turned off, the water in the pipes drains out through the lowest sprinkler heads and is replaced with air. The easiest way to tell if you have low head drainage is to watch the sprinklers when you turn them on. If they spit and spew lots of air when the valve is turned on, then you have a low head drainage problem. Obviously the water that drains out of the pipes is wasted. The spewing and spitting of air every time you turn on the sprinklers also puts a lot of stress on the pipe and sprinklers.

Leaking Valve or Low Head Drainage?

If you have water flowing from a sprinkler head continuously, even when the sprinkler system is off, then the problem is a leaking control valve. The primary difference between low head drainage and a leaking valve is that low head drainage results in water flowing from the lowest sprinklers for a while after they run, but the drainage stops after the pipes are fully drained. (It may take several hours for the water to drain out of the pipes.) If a valve is leaking the water will run out of the lowest sprinkler head all the time, 24 hours a day, every day. A typical indication that the problem is a leaking control valve is moss or algae growing on the sidewalk due to the constant flow of water. Another common sign is puddles of water around the lowest sprinklers that never dry out. To fix the leaking valve you must disassemble the valve, clean it, replace any bad parts, then reassemble it. See How to Repair a Irrigation Solenoid Valve for instructions. It is possible and common to have problems with both a leaking valve and low head drainage. Fix the valve first, then check for low head drainage.

How to Stop Low Head Drainage:

To fix low head drainage you need to have special anti-drain check valves installed at the sprinkler heads. These check valves prevent the water from draining out of the pipes through the lowest sprinklers. In most cases these check valves are built into the sprinkler head. The anti-drain check valve is an optional feature available when you purchase the sprinkler. This check-valve option is available on all major brands of sprinklers. The anti-drain check-valve closes and holds the water in the pipes when the sprinkler system is off. These built-in check-valves don’t cause any drop in performance of the sprinklers, so they don’t have any impact on your sprinkler system design. Many major brands of sprinklers can be retrofitted with a new internal check valve, although the retrofit kits are hard to find. Most pros simply buy a new head with the check valve feature and replace the old sprinkler with the new one.

You can also buy separate check valves that can be installed on the pipe under existing sprinkler heads. These are a lot harder to install, you need to dig up the sprinkler head, remove it, install the new check valve on the riser pipe, then screw the old sprinkler back into the new check valve. Then comes the hard part- the length of the check valve you just added makes the sprinkler sit about 3 inches higher than it was before! So now you need to lower the sprinkler head. There is also another catch to the retrofit type check-valves; they do result in a drop in the sprinkler’s performance. They typically create a drop in water pressure at the sprinkler inlet of 2 to 5 PSI. In addition to the performance drop the retrofit devices are often more expensive than simply replacing the sprinkler with a model that has a built-in check valve.

Where do you buy sprinklers with check valves or retrofit check valve? Check valves and sprinklers with built-in check valves are often not available at discount stores or big box hardware stores. You will probably need to get them from a local irrigation specialty store or online.

A tentative change to the language of the State of California’s Water Conservation Laws will make the use of low-drainage check valves mandatory for new sprinkler systems starting in the year 2010, and may also require retrofit of many older sprinkler systems with check valves. Expect other States where water conservation is an issue to also implement this requirement.

Irrigation and Expansive Soils

What is Expansive Soil?

Expansive soils can be found in many areas. Expansive soils expand in size when they get wet, and then shrink as they dry out. As the soil expands and contracts it can create enough force to cause major damage to building foundations, patios, and sidewalks. Expansive soils are also sometimes called shrink-swell soils, swelling soils, adobe, clay, or caliche soils. The damage caused by expansive soil is similar to that of frost heave found in northern regions, but it is NOT the same thing!

Identifying Expansive Soil

Soil that cracks or fractures when it dries is often a sign that it is expansive; however a lack of cracks does not necessarily indicate that the soil is not expansive. Other expansive soils take on a popcorn like appearance when they dry, they look like someone spread little lumps of popcorn shaped dirt on the soil surface. Expansive soils are often clay like, becoming very sticky when wet and hard and brittle when dry. The best way to determine if the soil at a location is expansive is to have an expansion test performed by a soil expert. Expansive soils are common in desert areas, and also in river bottoms or valleys formed by sediment. They typically form in areas that were once covered by seas or lakes. For example, they are commonly found in the deserts of Arizona, the valleys of Colorado, and coastal plains like the Los Angeles Basin and the low lying areas around San Francisco Bay. Often your local government building department can tell you if the soil in your area is known to have expansion problems. Links at the bottom of this page lead to websites with maps of expansive soil areas and more information on expansive soils.

Typical cracking of expansive soil when dry.

Limitations of this Article

Use of this information is at your own risk. Expansive soils vary widely so all I can offer here are broad ideas for ways to deal with it. You will need to decide for yourself the appropriateness of these ideas to your situation. If your soil is extremely expansive you should have a Soils or Geotechnical Engineer advise you on ways to deal with it (they are most often listed under the headings “Engineers – Geotechnical” and/or “Engineers – Soils” in your local phone directory.) Because of the extreme and costly damage that can result from soil expansion, you need to use extreme care in how you deal with it. Please see the Terms of Use for this website.

Water and Expansive Soils

Expansive soils either expand or contract as the amount of water or moisture in them changes. It doesn’t matter if the water is from rainfall or irrigation; the damage is the same either way. In a very simplified explanation, the soil pulls water into it, where the water is stored between the tiny soil particles. Since the water takes up space between the soil particles, the area occupied by the soil expands. The key to controlling damage is to keep the moisture level in the soil next to and under foundations, sidewalks or patios at a uniform level of moisture at all times. If the soil is dry, you want to keep it dry, if it is slightly wet, you want to keep it slightly wet. The amount of moisture in the soil isn’t nearly as important as avoiding changes in the moisture content of the soil.

Concrete Materials

When expansive soils are present it is important to use reinforced concrete to resist the soil movement. This is important because no matter how careful you are, there will be at least some minor soil expansion, and you must be prepared for it. Building and wall foundations should be designed by a qualified engineer. This is not a place to cut corners! Seek out qualified help for the design of foundations. Repair of building damage caused by soil movement can be horrifyingly expensive!

All concrete, including sidewalks and patios, should contain steel reinforcement materials such as rebar and steel mesh. Placing steel in the concrete strengthens it and reduces concrete heaving and cracking. Concrete patios should also have thickened edges with rebar in them to resist soil movement. A local licensed architect, landscape architect, engineer, or concrete contractor can advise you on the necessary thickness of the reinforced edge and the type and quantity of steel mesh and rebar to use. Be sure to discuss with them your budget, and how much cracking and heaving you are willing to accept. Often a compromise is required between cost and having a perfect concrete surface.

The use of concrete pavers or bricks is another option for patios and sidewalks in areas with expansive soils. The pavers are installed without mortar. As the soil expands and contracts the pavers simply move with the soil. The disadvantage of this is that the surface may become very uneven as the pavers move and shift. The advantage is that the pavers generally don’t crack like concrete. Another advantage is that if the pavers become uneven you can remove and reinstall them. Removing and reinstalling them is a lot of work, of course!

Controlling Soil Expansion

The most obvious way to keep expansive soils from expanding is to keep water off of them. Rainwater from roofs should be collected in gutters and then piped away from the building. Drainage should direct water away from buildings. The soil should slope away from buildings for at least 5 feet out from the wall, further is better. While this has nothing to do with irrigation, I mention it because it is important to keep all water away from the building, not just irrigation water. Also keep trees and large shrubs at least 10 feet from buildings as the roots can remove moisture from the soil next to the building and cause it to shrink and collapse.

One way that expansion of soils is controlled by architects and engineers is by mixing lime or other anti-expansion products into the soil. Irrigation water will leach lime and other materials out of the soil, which defeats the purpose of the treatment. Be sure to check to see if the soil under your foundation was treated with lime or a similar anti-expansion material prior to building the structure. If the soil was treated, you need to keep irrigation water away from the treated areas if possible. If possible consult with the building designer as to how far away you need to keep the irrigation from the treated area. If you can’t get a recommendation, keep the irrigation at least 5 feet away. Aprons around the building, as described further below, are a good solution when the soil has been treated.

Another way that engineers deal with expansive soil is to remove the soil and then reinstall it in severely compacted layers (usually with lime added), or just totally replace it with non-expansive soil hauled in from someplace else. This is fairly common in residential building. Normally the soil within 3 to 5 feet of the building foundation will be replaced to a depth of 4 or 5 feet. Be careful not to mix soil from elsewhere around the site with this soil. Also be careful not to mix soil amendments into this area as they will change the non-expansive soil properties. It is best to simply not plant anything within 5 feet of the building foundation. Remember that even if the soil around the building has been replaced or treated, you will still have to deal with expansive soil problems under your driveways, sidewalks and patios.